Economic Incentives Vital for Development of the Guiana Shield

By Odeen Ishmael

The fourth international congress on the biodiversity of the Guiana Shield, sponsored by the International Biodiversity Society of the Guiana Shield (IBG)[1] in conjunction with the Guyana government, was held during August 8-12 in Georgetown, Guyana.

In his address to the forum on April 8, Guyana’s President David Granger proposed a three-pronged approach to be adopted for the effective protection and preservation of the Guiana Shield. That approach, he said, must include the establishment of a scientific research institute, the setting up of strong mechanisms for data and information sharing, and adequate investment and funding.[2]

President Granger said that the scientific community, governments, non-governmental organizations and communities must forge partnerships to protect the Shield’s biodiversity, while allowing states to leverage its high endemicity, cultural diversity and intact ecosystems for inclusive growth and secure futures.[3]

The Guiana Shield

The Guiana Shield is a 1.7 billion-year-old Precambrian geological formation in northeast South America.[4] The higher elevations are the Guiana Highlands, with flat-topped mountains and are the source of some of the world’s most spectacular waterfalls such as Angel Falls and Kaieteur Falls. The Shield underlies Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana (Guyane) as well as parts of Brazil and Colombia. It has one of the highest biodiversity in the world, and is the natural habitat of numerous endemic species of mammals,[5] fresh water fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and insects.[6]

It also sustains one of the largest blocks of primary tropical rain forest worldwide as well as an eco-region marked by a very high biodiversity levels. With 90 percent covered with intact rainforest, the Shield plays a critical role in mitigating climate change and in regulating the water levels of the Amazon, Essequibo and Orinoco basins.[7]

As part of the wider Amazonian rain forest, the Shield’s protected areas include the Iwokrama Rain Forest of central Guyana, Kaieteur National Park, Kanuku National Park of southern Guyana, the Central Suriname Nature Reserve of Suriname, the Guiana Amazonian Park in French Guiana, the Tumucumaque National Park in Brazil’s Amapá State, and the Canaima, Parima-Tapirapeco and Neblina National Parks of Venezuela.[8] In 2014, Colombia designated a 250 hectare area of its section of the Guiana Shield, as a protected wetland.[9]

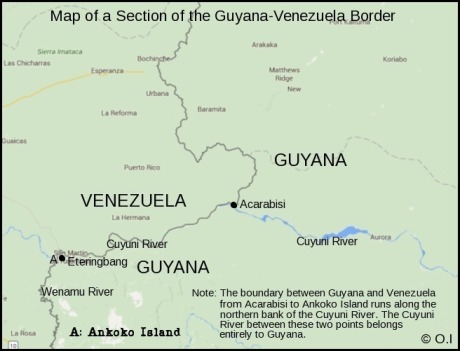

Map showing the Guiana Shield (Source: quoteco.com)

IIRSA projects for the Guiana Shield

As far back as 2006, the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (IIRSA)[10] unit of UNASUR[11] mapped out an ambitious road project for the Guiana Shield “hub” involving the infrastructural integration of eastern Venezuela (the states of Sucre, Anzoátegui, Monagas, Delta Amacuro and Bolívar), northern Brazil (the states of Amapá and Roraima), and the entire territory of Guyana and Suriname as well as French Guiana.[12] Part of this plan also includes a highway linking Ciudad Guayana in eastern Venezuela and Linden[13] in Guyana. The overall objective is to spur economic development in areas linked by this integration plan which has remained largely dormant over the past three years.

With an estimated area of 2.7 million square kilometers and a population of about 22 million, the Guiana Shield maintains a very low population density of just about 5 persons per square kilometer, and is one of the least developed areas in South America.[14] Even so, it has significant urban centers such as Manaos, Macapá, Boa Vista, Paramaribo, Georgetown, Ciudad Guayana and Ciudad Bolívar.

Economic sub-regions of the Shield

The Shield has two markedly different economic sub-regions, one with value-added production and relatively high population density, and the other, with abundant natural resources and a low population density. The more active economic section is located in eastern Venezuela with its petroleum industry and steel, aluminum and other manufacturing plants. The lesser developed area, which includes Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana and the Brazilian states of Amapá and Roraima, is developing at a slower pace with low value-added activities and contributes only about 12 percent of the hub’s GDP.[15]

Nevertheless, the lesser developed area has, overall, an immense developmental potential with its mineral, hydrocarbon, forest, and fishing resources, as well as immense hydroelectric capability and very large areas of under-exploited arable land. The territory also includes the Amazon ecosystems, vast savannahs, numerous rivers, waterfalls, mountains and extensive Atlantic and Caribbean coasts. These natural riches demonstrate a huge potential for tourism.

The integration of the road and transportation infrastructure will no doubt boost development at various geographical nodal points within the Guyana Shield hub. Already, with better road and river links between Manaos and other Brazilian population centers, that city has boosted its production of processed food, electronic goods, motorbikes and automobiles. A free zone has been established and the city now has a population of more than a million with several universities and research centers. Its growth, undoubtedly, has helped to generate economic development in the hinterland state of Roraima.[16]

Clearly, the Guyana government hopes that a similar pattern in the future can develop in the Rupununi region (bordering Brazil) as permanent road links are established with Brazil via the bridge across the Takutu River and, ultimately, the completion of the interior highway from Lethem to Linden and Georgetown.

It is obvious that the IIRSA communication plan for the Guiana Shield countries cannot be fulfilled in the short-term. But a start has already been made, and incremental implementation is expected to follow. Ultimately, the political commitment of the respective governments will determine how successful it will be.

REDD+ for the Guiana Shield

Currently, the countries of the Guiana Shield are pursuing policies that emphasize the importance of establishing biodiversity corridors to avoid landscape fragmentation and loss of species and habitats for biodiversity. At the same time, these policies are aimed at protecting the rights of the indigenous Amerindians to their territories and of access to their natural resources, in order to preserve their livelihoods and cultures.

Until the end of the twentieth century, the Guiana Shield forests were under little threat in comparison with other tropical forests. However, demographic and economic growth has increased pressures on the natural ecosystems. Since governments prefer to advance national development in a sustainable manner, they have shown strong interest in the United Nations Collaborative Program on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+)[17] +) through which they would be able to financially value their efforts in protecting their forests and at the same time acquiring carbon revenues from participating developed countries. This program was launched in 2008.

The project, “REDD+ for the Guiana Shield,”[18] was initiated first by Guyana, Suriname, France (for French Guiana), and the Brazilian state of Amapá. It aims to prevent deforestation and degradation within the framework of the REDD+ mechanism.

REDD+ for the Guiana Shield is funded by the Regional Development European Fund (FEDER) through the Interreg IV Caraibes program (1.26 million euros)[19], the French Global Environmental Facility (1 million euros), the French Guiana Region (90,000 euros), as well as by the project partners own contributions.[20]

Guyana-Norway forest agreement

In Guyana’s case, the country was promised US$250 million under the multi-year forest protection agreement with Norway signed in 2009.[21] This was shortly after Guyana established the Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS),[22] under the presidency of Bharrat Jagdeo, to fashion by 2020 a new low carbon economy geared toward reducing carbon dioxide emissions, and promoting economic and cultural projects to minimize the effects of climate change.

By 2015, Guyana was credited with over $190 million from this arrangement, $70 million of which has been deposited into the Guyana REDD+ Investment Fund (GRIF). A sum of $5.8 million was disbursed to the Guyana Forestry Commission to assist with development of the monitoring, reporting and verification system, and $80 million has been directly transferred to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) for the government’s equity in the Amaila Falls hydro-electric project[23]—a project forming an integral part of the LCDS—which was unfortunately jettisoned[24] by the new government which came to power in May 2015. A further $40 million is pending having been announced in May 2015.[25]

More recently, the Guyana government has stated its interest in resuscitating the hydro-electric project[26] but has also revealed that it will lose US$18 million from the agreement with Norway. This financial loss comes as a result of penalties for not meeting certain indicators specified in the agreement, as well as from losses due to adjustments in the exchange rate between the Norwegian kroner and the US dollar.[27]

Need for investment

The sustainable development of the area encompassing the Guiana Shield should be a priority for the countries of that geographical region. The area provides essential environmental services to all of humanity and, as such, economic incentives are vital to ensure that the forests remain in a pristine state. As President Granger said during his address[28] to the international congress, the absence of investment will place pressures on the governments of the Shield, particularly the three smallest states, if they move to exploit the region’s natural resources. The developed countries must realize the necessity of the sustainable development of this region and their inputs in the form of tangible investments can go a long way in preventing deforestation and destructive mining, as well as in preserving the biodiversity of the area.

August 22, 2016

(Dr. Odeen Ishmael, Ambassador Emeritus (retired), historian and author, served as Guyana’s ambassador in the USA (1993-2003), Venezuela 2003-2011) and Kuwait and Qatar (2011-2014). He actively participated in meetings of UNASUR from 2003 to 2010 and has written extensively on South American integration issues. He is currently a Senior Research Fellow of the Washington-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs.)

References:

[1] http://www.biodiversityguyana.org/ibg2016congress/

[2] http://gina.gov.gy/president-outlines-three-pronged-approach-for-protection-management-of-guiana-shield/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Lujan, Nathan K.; Arbruster, Jonathan W. (2011). “13: The Guiana Shield”.

In James S. Albert and Roberto E. Reis. Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes (PDF).

The Regents of the University of California.

[5] Hollowell, T.; Reynolds, R.P. (2005). “Checklist of the Terrestrial Vertebrates of the Guiana Shield” (PDF). Bulletin of the Biological Society of Washington.

[6] Costa, Mauro; Viloria, Ángel L.; Hubber, Otto; Attal, Stéphane; Orellana, Andrés (2013).

“Lepidoptera del Pantepui. Parte I: Endemismo y caracterización biogeográfica”. Entomotropica. 28 (3): 193––217. .

[7] https://reddguianashield.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/1st-working-group-report.pdf

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guiana_Shield

[9] http://www.ramsar.org/es/complejo-de-humedales-de-la-estrella-fluvial-in%C3%ADrida-efi

[10] https://www.oecd.org/site/govgfg/39612363.pdf

[11] UNASUR was then known as the Community of South American States.

[12] http://www.guyana.org/commentary/commentary_022207.html

[13] http://www.iirsa.org/admin_iirsa_web/Uploads/Documents/mer_bogota04_presentacion_eje_del_escudo_guayanes.pdf

[14] http://www.guyana.org/commentary/commentary_022207.html

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] https://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/what-redd

[18] https://reddguianashield.com/

[19] In 2008, the euro was equivalent to US$1.50. Its value has declined since then.

[20] Ibid.

[21] http://theredddesk.org/markets-standards/guyana-guyana-redd-investment-fund-and-norway-partnership

[22] http://www.lcds.gov.gy/

[23] http://theredddesk.org/countries/initiatives/amaila-falls-hydropower-project

[24] http://www.hydroworld.com/articles/2015/08/guyana-nixes-plans-for-165-mw-amaila-falls-hydropower- project.html

[25] http://www.climateandlandusealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Impacts_of_International_REDD_Finance_Case_Study_Guyana.pdf

[26] http://gnngy.com/amaila-falls-project-could-be-resuscitated/

[27] http://demerarawaves.com/2016/07/20/guyana-loses-us35-million-from-norway-forest-protection-deal/

[28] http://www.biodiversityguyana.org/ibg2016congress, op. cit.